A lot of questions about how to have sex, how to masturbate, and worries about all of what’s all going on down below can be easily solved by simply getting to know what genitals and other reproductive organs are all about. Many things some people presume are problems with some kinds of sex or genital function or appearance are just realities of anatomy they didn’t know.

Here’s a starter scoop for many people whose bodies have what are most often called a vulva, vagina, labia, clitoris and/or uterus and other structures. There’s no one single way all genitals look or even are put together, and not everyone with some of these parts will have all of them. You also don’t have to call them the scientific names they’ve been given unless you want to. We just use those words to make things easiest for everyone around the world to understand.

If you have some privacy, time, and it’s right for you, you can get yourself a mirror and give yourself a guided tour of your body with this article as you read it.

Vulva, not vagina

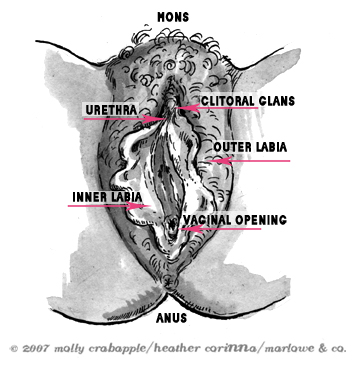

The scientific name for these external genitals is the vulva (vuhl-vah). The vagina isn’t actually part of the vulva, save its opening. Some people learned to call the vulva the vagina instead.

The scientific name for these external genitals is the vulva (vuhl-vah). The vagina isn’t actually part of the vulva, save its opening. Some people learned to call the vulva the vagina instead.

Where the pubic hair is, below your belly button, is a fatty area of tissue (skin) called the mons (mahns). Your pubic hair usually, if you don’t mess with it, covers the mons, and moves downward, as will that fatty tissue, around your labia majora (lay-bee-ah), which some people call “lips.”

If you pull the outer labia open, you’ll see the labia minora, which are not covered with hair, and look a bit like flower petals or small tongues. The size, length and color of the inner labia and other parts of the vulva differ from person to person. The labia may be long and thick, or barely visible, and may look purple, red, pink, black or brown, depending on your own coloring. All of these variations are absolutely normal, as are the labia being two different sizes or shapes. The purpose of your inner labia is important; they have sensory nerve endings which contribute to sexual pleasure and also keep icky bacteria away from what is called the vestibule.

The Infamous Clitoris

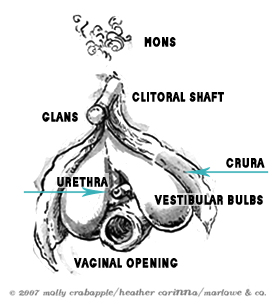

Looking at the vestibule, between those inner labia from the top down (right below your mons), you’ll first see the top of the inner labia, which create a little skin fold called the clitoral hood. That hood connects to the glans, which is the tip – and only the tip – of the clitoris (klit-or-iss). If you pull up the hood with your fingers, you can get a closer look if you like.

The clitoris – which in full, internal and external, is nearly about the same size as the penis – is usually the most sensitive area of, and involved in the most sensitive areas of, the vulva and vagina. It interacts with over 15,000 nerve endings throughout the whole pelvic area. It is created of the same sort of erectile tissue that the head of a penis has. Before we all were born, until about the sixth week of our lives as an embryo, our sexual organs were slightly developed, but completely the same no matter our sex or gender.

If you feel the clitoral glans with your fingers, you’ll probably feel a tingle or a tickle. Rubbing it a bit or pressing down on it, you can feel a hardish portion that is the shaft of the clitoris. The whole of the clitoris is the primary source of most genital sensation for these kinds of genitals. The clitoris is, in fact, the only organ on the entire body that is solely for sexual arousal, and is attached to ligaments, muscles and veins that become filled with blood during arousal (when you get sexually excited) and contract during orgasm. The clitoris is what most like to have stimulated in some way during oral or digital (with hands and fingers) sex, during masturbation, and during intercourse, and not just the tip or shaft. The clitoris is internal as well as external – and the whole thing is a lot bigger than it looks from the outside – with legs, called crura, that are within the outer labia, as well as the clitoral (or vestibular) bulbs, which surround part of the lower portion of the vaginal canal.

If you feel the clitoral glans with your fingers, you’ll probably feel a tingle or a tickle. Rubbing it a bit or pressing down on it, you can feel a hardish portion that is the shaft of the clitoris. The whole of the clitoris is the primary source of most genital sensation for these kinds of genitals. The clitoris is, in fact, the only organ on the entire body that is solely for sexual arousal, and is attached to ligaments, muscles and veins that become filled with blood during arousal (when you get sexually excited) and contract during orgasm. The clitoris is what most like to have stimulated in some way during oral or digital (with hands and fingers) sex, during masturbation, and during intercourse, and not just the tip or shaft. The clitoris is internal as well as external – and the whole thing is a lot bigger than it looks from the outside – with legs, called crura, that are within the outer labia, as well as the clitoral (or vestibular) bulbs, which surround part of the lower portion of the vaginal canal.

Getting back to the outside and looking lower, you may be able to see another hood-like shape. Right below that shape is a teeny, tiny, barely visible little dot or slit, which is your urethra or urinary opening, where you urinate (or pee) from. Below that is the vaginal opening. You might notice how close the urinary opening is to the vaginal opening. Because of this, sometimes sexual activity can bring bacteria which infect the urinary opening, so it’s important during sexual activity to both empty your bladder before and after, and to be sure your or your partner’s hands, mouth or other organs are clean.

Just barely inside the vaginal opening, you may see the vaginal corona or portions of it. Your corona may or may not be easily distinguishable from the rest of your vaginal opening, and that isn’t always because of sex. Long ago (and still sometimes today) it was thought that the corona (formerly known as the “hymen”) was “evidence” of whether or not a woman had had sexual intercourse, but that is not the case at all. Not even all people with vulvas are born with intact or easily identifiable vaginal coronas! When someone is talking about “popping a cherry,” this is what they are referring to, though it’s a misnomer. Sparing injury, the corona usually just erodes gradually and pretty unnoticeably over time. Even when it is more intact, it rarely covers the vaginal opening completely, but instead still has little holes and perforations in it. After it has been mostly worn away or stretched, small folds of tissue often remain. For more about it, check out: My Corona: The Anatomy Formerly Known as the Hymen & the Myths That Surround It.

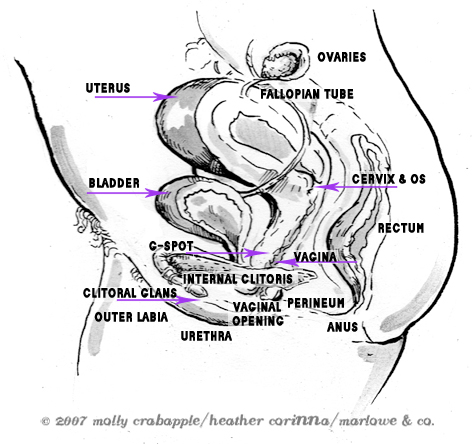

If you can and want to slide your finger into your vaginal opening, you can squeeze your vaginal walls (engaging what are commonly called PC – pubococcygeus: that’s pee-oobo-cocko-gee-us– or Kegel muscles), just like you were trying to hold it in when you have to pee and there isn’t a restroom nearby. You can feel folds of skin and different textures, and see how the vagina (which is the passage between the vaginal opening and the cervix holding your finger there like a tube) can hold your fingers. That is the same way it holds a tampon, a penis or toy, or a baby during labor.

Your vagina may be wetter or dryer right now depending on your menstrual cycle. If you’re someone who menstruates and ovulates, then right after you’ve had your period, or when you aren’t aroused, you’ll generally be dryer, and about two weeks into your cycle, or when you are aroused, you’ll usually be a bit wetter. The mucus, or “discharge” from your vagina, which you’ll sometimes see on your underpants, may vary in texture, scent and color greatly. Some people are freaked out by this, but there is no need to be, and trying to get rid of that mucus with douching or other methods is not healthy, as that mucus keeps your vagina clean of bacteria and maintains a careful acid balance vital to your health. If you’re ever in doubt about vaginal discharge, the best thing to do is to talk to a healthcare provider. In general, however, unless the mucus is spotted with blood and you aren’t on your period, makes you itch at all, or is greenish in hue, it’s probably healthy, normal discharge.

Life on the Inside

Inside your vagina, towards your belly, not your back, there’s a spongy area that is a bit like the roof of your mouth in texture (you may be able to feel it with your fingers, but if you have short fingers, you may not be able to). That area is what many people call the G-spot, or Grafenburg Spot, another potential source of, or contributor to, sexual pleasure or orgasm. It’s another portion of the internal clitoris and urinary system. The vagina itself, especially past the first, front 1/3rd of it, has hardly any sensory nerve endings at all. The sensations people feel inside the vagina are often more about the external and internal clitoris or stimulation of the cervixexternal link, opens in a new tab than the vagina itself.

That area or spot isn’t a magic button, or any kind of button at all, it is simply a potential area of your genital anatomy that may be responsive to stimulation and give you pleasure. Or not.

More deeply inside the vagina, upwards and towards the back, is something that feels a bit like a nose or a dimpled chin. This is the cervix, the base of the uterus. The cervix is the passage through which sperm travel to meet an egg in the fallopian tubes, but don’t worry – nothing but sperm can usually fit in there. In other words, you can’t “lose” a tampon or a toy or anything else in your vagina, because it ends with your cervix.

The very back of the vagina, slightly above and around the base of the cervix, is called the fornix. During sexual arousal, the fornix gets larger, or “tents,” to make extra room for whatever might be inside the vagina.

Inside the body, the cervix leads into the uterus, which some people call the womb. It’s a very muscular organ that, when nothing is inside of it, is only about the size and shape of a small pear, a fact which may be very surprising, since bad menstrual cramps make it feel the size of Omaha, Nebraska. It’s where a fetus develops and grows if and when someone gets pregnant and sustains the pregnancy. The lining of the uterus, called the endometrium, builds up every menstrual cycle, and this is what gets shed each cycle with a menstrual period. For more about that, check out: On the Rag: A Guide to Menstruation.

On either side of the uterus is a fallopian tube. Eggs travel through the fallopian tubes, also called the oviducts, to get to the uterus. Fingerlike structures called fimbriae at the end of the fallopian tubes sweep the eggs from the ovary into the tubes. At the end of each fallopian tube is an ovary, which both stores and releases eggs, or ova, one at a time during each menstrual cycle (though some people may ovulate more than once in a cycle, and some may sometimes release more than one egg at a time). For more on all that, see: Human Reproduction: A Seafarer’s Guide.

The ovaries produce the hormones estrogen and progesterone, which do a lot of things throughout the body, including helping to keep the genitals flexible, elastic, and lubricated and help keep the vaginal lining healthy. Some estrogen is also produced by fat tissue. The hormone testosterone is also produced in the ovaries (and by the adrenal glands elsewhere in the body).

Right under your vaginal opening is a flat length of skin called the perineum (pair-ee-nay-uhm). Below the perineum is your anus.

The anus is the opening to your rectum, through which your bowel movements pass through from your bowel. Some people enjoy incorporating their anus into their sexual lives. Some people do not. The important thing to recognize is that there’s nothing any more icky or gross about the anus than there is, say, the mouth. A lot of people have a lot of shame about their rectums and anuses, and that can sometimes play a part in how they manage their sexual choices or their health.

Some things to know are that feces (bowel movements) are not stored on the anus or in the rectum. Only trace amounts of feces may remain there. Another thing to know is that the anus does not have any natural lubrication of its own, and the anal tissues are far more delicate and susceptible to tearing than the vaginal tissues. That makes anal sex potentially painful and unsafe if not done with extra care.

Above all else, understand that your genitals are really no different from any other part of your anatomy: parts is parts. They aren’t something to be ashamed of or embarrassed about, and in many cultures our genitals are thought of as sacred instead of yucky, scary or sinful, as they’ve historically so often been presented where we write from here in the colonized West. Treat them with honor and care, let them bring you joy and do your best to try and care for and accept them with the rest of your body.