“Machismo” has dreadful roots in Latin based cultures, and is strongly associated with many men’s identities, Latin society and its expressions. Its name derives from the Spanish and Portuguese word “macho” which means male. Machismo is an expression of exacerbated masculinity that has caused lingering pain and trauma to generations of Latinx people. Many young people are still struggling with it today.

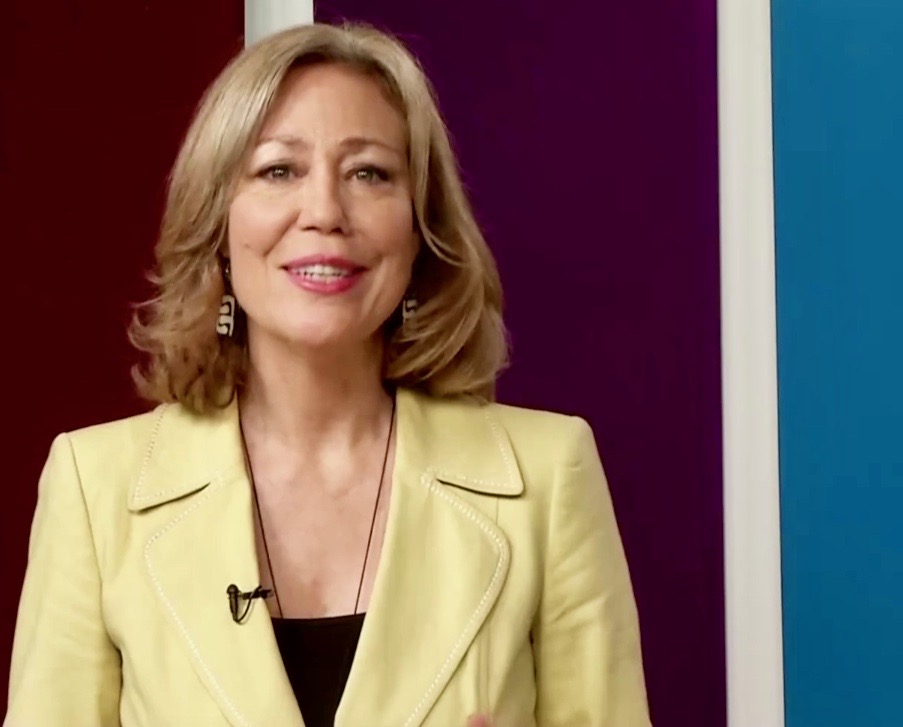

Journalist and scholar Laura Carlsen directs the journalistic site Americas Programexternal link, opens in a new tab, focused in Latin Americaexternal link, opens in a new tab’s foreign policies and the countries’ relations to the USA. She has studied and lived in Mexico city since 1986. In her line of work, Carlsen has to deal with machismo from politics to femicides. She’s dealt with it as it’s spilled into newsrooms where female reporters are bullied and sexually harassed by editors and colleagues, and while gender violence as femicide are treated in some media channels as day to day “sexual assaults” or romanticized as “crimes of passion.” Scarleteen spoke to Carlsen to further understand machismo and the damages it can cause.

Scarleteen (ST): Can you define machismo and its characteristics?

Laura Carlsen (LC): It is commonly considered an exaggerated expression of masculine identity, but I’d say it’s more a deformed expression of masculine identity constructed to perpetuate and strengthen male dominance over women. It is expressed in brute force, that is, violence against women that confirms a submissive and discriminated role and denies physical and emotional autonomy; in oppressive attitudes that belittle, intimidate, and humiliate women and children; and social characteristics that encourage all of the above, especially in groups of men.

ST: What differentiates machismo from sexism?

LC: Sexism refers more to the structural system and is not directly tied to male character expressions and identities.

ST: How is machismo in Latin America different from the rest of the world?

ST: How is machismo in Latin America different from the rest of the world?

LC: It’s no coincidence that the word for a stereotypical male-dominated culture is “machismo,” derived from the Spanish word for male and originating in Latin culture. Today in Latin American cultures, machismo is still considered the accepted norm by most of society whereas in other countries at least there is a recognition that, like racism, it is a form of discrimination that should be overcome.

As a direct result of the acceptance of machismo, or male-domination, Latin American countries have the highest rates of violence against women in the world. Also, the world’s citiesexternal link, opens in a new tab with the highest homicide ratesexternal link, opens in a new tab in general are located here (According to a 2018 report from Igarapé Instituteexternal link, opens in a new tab Latin America has 8% of the world’s population, but 33% of its homicides and four countries in the region – Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and Venezuela – are home to a quarter of all the assassinations on the planet). When a heavily macho culture is combined with weak institutions, faulty justice systems and easy access to firearms, like it is in our region, the result is lethal - for women, children and men.

ST: Are there social or cultural catalysts of that violence?

LC: There is a long history of not only acceptance of male violence and male domination, but of celebration of it. A man who has a more equal relationship with his wife or girlfriend is ridiculed as a “mandilón” (literally, “tied to her apron strings”). Motherhood is accompanied by reinforcement of traditional gender roles and strong barriers against women in the public sphere.

Men’s control of the family economy and often of women’s bodies creates decencies that maintain women’s submission. It’s a reinforcing cycle that despite greater awareness and some public policy to counter it, continues to remain strongly in place. In fact, we’re seeing many signs instances of regression, with the emergence of new fundamentalist movements and rollbacks in women’s legislative gains.

ST: Do you think the societies that lived here before the conquistadors were also sexist?

LC: It’s impossible to talk about all pre-Hispanic (indigenous) societies as one because they each have their own cultures and societies. Anthropologists generally agree that to portray the colonialists as the origin of machismo is wrong–that gender inequality existed in most pre-Hispanic societies. However, there are also many ways in which women were less oppressed and there are many aspects of these societies that we are still learning about. One constant seems to be that with the rise of militarismexternal link, opens in a new tab comes greater subjugation and exclusion of women.

ST: Has it diminished as time went by or is it still very strong?

LC: It is still very strong and as I mentioned in some ways getting stronger. We have laws, such as electoral gender quotas that have increased the number of women in politics but the manipulation of these laws is widespread and cynical.

In Mexico, a large number of women candidates ceded their elected positions to their husbands after taking office and we had a recent case of parties registering men as transgender to fill women’s quotas despite the fact these people had never before identified as such.

ST: Is there any correlation between machismo and religion?

LC: Yes, the Catholic church hierarchy in many countries and evangelicals have initiated orchestrated offenses against women’s sexual and reproductive rights as part of what they call “family values”external link, opens in a new tab that by keeping women and girls from reaching their full human potential and encouraging violence do immeasurable damage to families.

ST: Can you talk a bit more about the correlation between machismo, the Catholic church, and the policing of women’s bodies (particularly their sexual and reproductive health)?

LC: I’m thinking of the Evelyn Hernandez trial, which had a relieving outcome but was still a vicious case nonetheless. (Salvadorian Ms. Hernandezexternal link, opens in a new tab was prosecuted for aggravated homicide based on an obstetric emergency she went through while birthing her child).

ST: During demonstrations in the USA of white male supremacy in 2018external link, opens in a new tab we saw some men with T-shirts making references to the deadly helicopter rides done by the Chilean dictatorial government to throwsome of those who oppose them out of airplanes to hide their deathsexternal link, opens in a new tab. Is there an intersection between white male supremacyexternal link, opens in a new tab and machismo?

LC: Yes. What’s interesting here is that there is an assumption that opposition to white male dominance can and should be annihilated.

ST: How does machismo affect Latin American politics?

LC: In a number of ways. It is a cultural current that serves to repress feminist movements and campaigns for women’s rights and justify male supremacy. It openly validates discrimination by creating cultural expressions in music, literature, film etc. that set out macho role models that assure its reproduction in the next generation, stunting the emotional growth and human potential of children both male and female. It operates on the basis of dualisms that construe differences as battles for dominance and require active suppression of any human expression that threatens male supremacy.

ST: How does machismo affect your journalistic work and observations of Latin America?

LC: Machismo poses a huge challenge to women journalists. Issues that mostly affect women are ignored or buried by editors, gender violence is trivialized as sexual assault and even assassination of women are justified in the language as “crimes of passion”. we have to struggle to be treated equally as reporters and analysts and face widespread sexual harassment on the job. With high levels of violence against journalists, women journalists face specific threats of sexual violence along with general threats, and not only against them, but against their families.

In Mexico, the tragic and unsolved murder of Miroslava Breachexternal link, opens in a new tab sent a chilling message to women reporters regarding the risks we face. Lately women have been organizing groups of women in journalism to confront these barriers and force the media to be more responsive and adopt protection measures. These groups are important but incipient and still striving to change an industry that is deeply sexist.

ST: Is there any way to extricate machismo from “family values”?

LC: They are completely the opposite. Machismo is statistically the greatest threat to the safety and health of families since rates of male violence affect children’s and mothers’ health, physical integrity, emotional well-being, economic stability, etc.