Today, we talk about history, and the ways in which it can be complicated. This isn’t news for queer and trans people of color — the fact that our experiences and communities are built on historical tragedies and injustices is deeply rooted within our bodies and our daily interactions. Often we can’t turn around without being reminded of the ways in which intersecting oppressions weave together to create the systems that govern our lives.

But today I write as someone with a passion for comprehensive sex education, reproductive health access, and health literacy. I love my fields and the work that I do more than anything, and I think that everyone should care about it as much as I do. But my love for talking about clitorises, IUDs, yoga mats, therapy appointments, condoms, and porn can’t stop there — I also have a responsibility as an educator to talk about the ways in which my work is built on some incredibly problematic and unethical foundations.

Enter J. Marion Sims, M.Dexternal link, opens in a new tab.

J. Marion Sims was a doctor who practiced medicine in the 1840s in Montgomery, Alabama. He is widely considered to be the “father of modern gynecology” due to the treatments he developed to help repair damage to the rectum and vagina that often happened after traumatic childbirth. He is responsible for inventing the precursor to the modern vaginal speculum, and created several new effective surgical interventions, but the way he did it was far from ethical — he experimented on enslaved women.

J. Marion Sims was a doctor who practiced medicine in the 1840s in Montgomery, Alabama. He is widely considered to be the “father of modern gynecology” due to the treatments he developed to help repair damage to the rectum and vagina that often happened after traumatic childbirth. He is responsible for inventing the precursor to the modern vaginal speculum, and created several new effective surgical interventions, but the way he did it was far from ethical — he experimented on enslaved women.

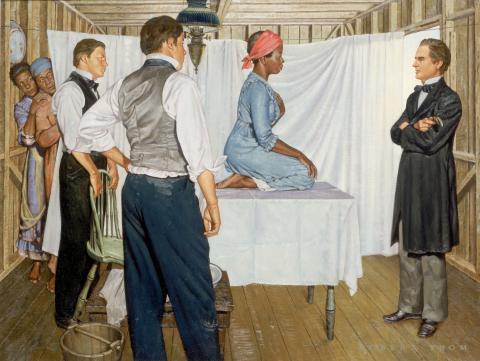

Between 1845 and 1849, Sims operated on a group of 10 enslaved people who had been “lent” to him under the condition that their owners pay for their clothing and food in exchange for medical care. In his writings, he only named three of them — Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey. He performed dozens of surgeries on these women, often under observation by other doctors and surgeons. To the left, you’ll see one of the most famous depictions of this, in which one of the women is sitting on a table, eyes cast downwards, surrounded by men (including Sims himself). Two other women peek around a sheet that has been set up to create the “observation room.”

Sims insisted he got consent from the women, and that he only wanted to improve their quality of life, but these statements have to be put into context. These women were enslaved people, and considered to be property. A surgeon asking if you’d be willing to undergo a medical experiment when a slaveholder has handed you to him for the purpose of experimentation is a far cry from the empowered, capable, informed consent that we strive to obtain in modern-day treatment settings.

What’s worse, he did so without the use of anesthesia. There is some debateexternal link, opens in a new tab about whether that was an intentional, racism-based choice, or just a fact of the time period, in which anesthesia was not commonly used, but we cannot deny that these enslaved people were denied their basic rights to liberty, autonomy, and privacy, much less the quality and ethics of modern-day gynecological care. During the late 1800’s, it was a widely-held belief that black bodies felt less pain than white ones did, a belief that wasn’t based on anything other than white supremacy thinly veiled as pseudoscience. Unfortunately, this belief has been sustained throughout the centuries, and while it and other bigoted attitudes are becoming less overt, they remain in common unconscious bias. This translates into real, everyday consequences, especially when those who have the unconscious biases maintain powerful positions in universal societal structures like the field of medicine. A study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2016external link, opens in a new tab showed that of the 418 medical students interviewed, the ones that held false beliefs about biological differences between the races were more likely to rate black patients’ pain as lower than white patients’. These toxic underlying beliefs lead to black patients getting worse quality of care, including less pain medication than their white counterparts.

NPR did a piece on this dark history in 2016external link, opens in a new tab in which medical historian Vanessa Gamble and poet Bettina Judd discussed the ways Sims’s behavior and discoveries shaped gynecology and the wider practice of medicine for better or for worse. Stories like the ones that Judd share help me to think about the ways historical events like this have affected how the bodies and sexualities of people of color are perceived and treated. They also push me to try to ground my work in a constant effort to try to understand more, to engage more, and to fight against historical oppression and silencing of women and trans folks of color.

Earlier this year, some of the folks over at Black Youth Project 100external link, opens in a new tab, in an act of symbolism and solidarity, protested in stained surgical gowns in front of the statue of J. Marion Sims across the street from the New York Academy of Medicine, one of several that honor his accomplishments in his hometowns and alma maters. They want justice for the women who were unethically treated in all areas of life, whose bodies and pain gave way to the modern advancements in medical technology that have grown to improve and save the lives of so many others. I am grateful for the work they do to raise awareness about these issues, and for the reaffirmation that it gives me about my own commitment to reflect on the complicated histories of sex and sexuality work while striving to create more transparent and accessible futures.

J. Marion Sims, “father of modern gynecology”, memorialized for performing genital surgery on Black woman slaves w/o anesthesia or consent pic.twitter.com/p5hE8S7uCvexternal link, opens in a new tab

— BYP100 (@BYP_100) August 19, 2017external link, opens in a new tab

Know of a blog, organization, or resource that belongs here? Send it to our curator, Al (that’s me!), at al AT scarleteen DOT com. Interested in contributing as a guest writer for our Sexuality in Color series, or any other part of Scarleteen? Check out our information for writers and then take it from there! Experienced queer and trans writers of color of varied abilities and backgrounds are always strongly encouraged to apply.